Today, almost 150 years since the end of slavery, two-story slave cabins still stand prominently on the grounds in Durham County, but that is not the case for hundreds of former slave structures across the U.S.

An organization called sets out to identify these mostly small, dilapidated structures and bring attention to their preservation by inviting people to sleep in them. Reporter Leoneda Inge spent this past weekend at Stagville.

sits in the middle of what was once one of the largest slave plantations in the south. As many as 900 slaves worked the land owned by the Bennehan and Cameron families.

Jessie Eustice walks visitors through the Bennehan House, and then to the slave quarters about a country blaock away.

“So a family would live in one room and it would consist of between 5 and 12 people,” said Eustice.

The tourists are pretty quiet, taking it all in. Lusie Hirsch lives in Germany and is visiting friends in Durham.

“I have been to plantation homes before, that was nearly 20 years ago, and they paid practically no attention to the enslaved people. So this is the first time I am getting an in depth view of how they lived," said Hirsch.

I asked Hirsch if she would spend the night in a slave dwelling.

"I would consider doing it if the weather was tolerable and if I wasn’t by myself," said Hirsch. " I guess that is one thing that we tend to forget, these people never had a moment to themselves.”

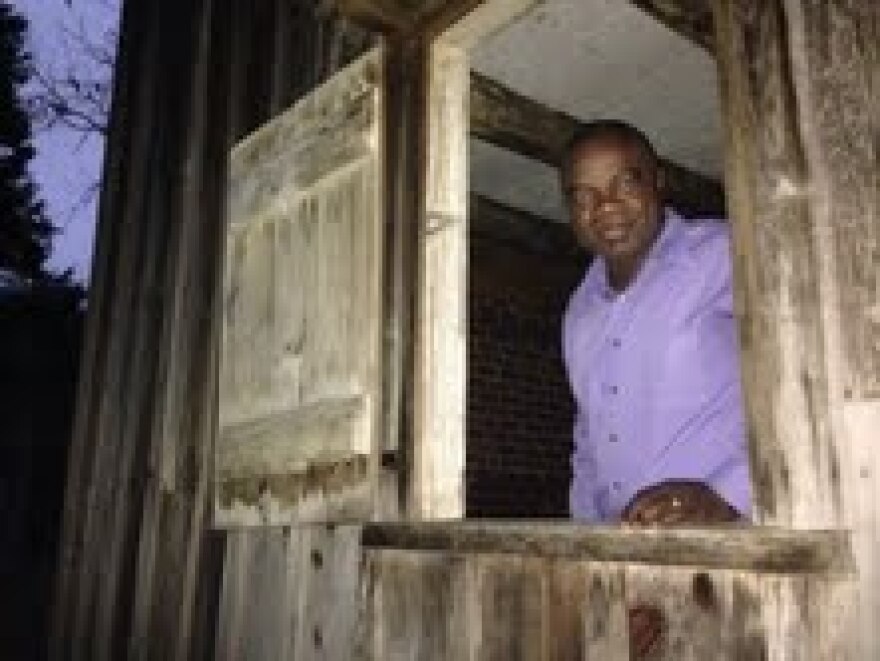

As the Saturday tour ended, another small group arrived. We were about to get very intimate with one specific structure on the Historic Stagville grounds. We were preparing to spend the night with Joseph McGill. He has worked with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and is founder of the Slave Dwelling Project.

“There has been a tendency not to concentrate on those, not to preserve those. Not preserving those, they deteriorate and or torn down, sometimes with malicious intent, and that intent is to erase that part of our history," said McGill.

McGill has slept in almost 50 former slave dwellings across the country. He loses count. And he says there’s no telling what some of these dwellings have become.

“Some exist as storage areas, some exist as guest houses, pool houses, storage spaces, and some are primary residences for people," said McGill.

McGill says sleeping in a slave dwelling is a lot to ask someone to do. And still they do it, like Prinny Anderson of Durham. This was her fifth time sleeping in a slave dwelling.

“It was the kind of action I wanted to take to honor the enslaved people that my ancestors had owned and did not honor and have not honored in the meantime," said Anderson.

Anderson can trace her family back to Thomas Jefferson. Terry James has also traced his family roots – all the way back to a plantation in Florence, South Carolina. He has slept in a slave dwelling with McGill nearly 20 times, each time with his wrists shackled.

"Tender here then you try to twist the other way, and the next day actually I was sore from trying to sleep. My hips were sore and my back was sore," said James. "I still do it, kind of paying tribute to those people who came over and suffered and died.”

Three graduate students from North Carolina Central University also joined us for the night - Charles Harris, Deidre Brooks and Jermara Bullock. To help ensure a decent night’s sleep Jerome Bias cooked dinner on our camp fire.

“This is succotash, this is, okra, just how my grandmother used to make it,” said

We stretched out dinner and conversation for as long as possible. A lot of the talk centered around race, from the Underground Railroad to the movie, “The Butler.” Jeremmiah DeGennaro, Assistant Site Manager at Stagville, also stayed over, and let us use the facilities in the Welcome Center one more time before heading to bed.

There were eight of us in one room, a room meant for one slave family. There was a lot of tossing and turning, and snoring.

Finally, the sun peeped through the open space that serves as a window, and roosters crowed. It was time to pack up and go. No one really had a good night’s sleep, but we weren’t expecting to.

Joseph McGill.

“Sleeping is just not enough. Now it’s time to wake up. Now that the attention has been garnered, now I can deliver the message that these places are important," said McGill.

The Slave Dwelling Project has scheduled its first conference for next fall. McGill has invitations to keep hosting sleep-ins at slave dwellings for the next two years.