Just as substance use experts celebrated a somewhat mysterious drop in drug overdose deaths across North Carolina, Hurricane Helene blew through the western part of the state, causing death and widespread property damage. In the storm's aftermath, many residents found themselves without homes and businesses and facing an uncertain future.

For harm reductionists like Hill Brown, the southern director of , Helene's impact raised serious concerns. Brown knew that the disruption to the local drug supply, coupled with the stress of losing housing, could lead to an uptick in overdoses in the coming months.

Over the past month, Brown, who lives in western North Carolina, has been pushing to get the overdose reversal drug, naloxone, into the hands of more people. Brown said she was surprised to find that some rural areas that had previously resisted harm reduction efforts, including naloxone distribution, have begun to embrace these life-saving tools in the wake of Helene.

“Once the [drug] supply comes back online, and people haven't had good access to their dealers or to whatever supply they were using, there is going to be an uptick in overdoses, because we just don't know what the supply is going to look like," Brown said.

"If we're talking about a crisis where lots of people are losing their housing, or their housing is becoming unlivable because of flooding, then people are going to be stressed out, and they're going to do things that they know how to do to cope.”

This threat comes when the overdose crisis in North Carolina has shown signs of improvement — at least on paper. The predicts about a 30 percent decrease in overdose deaths in North Carolina from May 2023 to May 2024, a statistic that will be confirmed once death certificates are finalized.

Nationally, the CDC estimates roughly a 13 percent decrease in overdose deaths for the same time period, based on provisional death data.

These numbers will likely shift because the data is incomplete right now, and North Carolina has been particularly slow in reporting its overdose death data to the federal agency, according to a note that initially topped the latest CDC report. Spokesperson Summer Tonizzo, with the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services, told NC Health ����app that this is an indication that North Carolina has a high number of “pending” deaths.

“These are cases being investigated by NC’s Medical Examiner System which continues to struggle with rising caseloads and staff vacancies — both of which have negatively impacted the system’s ability to timely close pending death records,” Tonizzo wrote in an email.

Even so, North Carolina epidemiologists say, all indicators point to a significant decrease in overdose deaths. But as they dig into the data, a more complex picture emerges — one marked by uneven progress and disparities affecting marginalized communities.

Cautiously optimistic

Those ongoing pressures in the medical examiner system means it takes a long time to certify death reports that go through the state’s medical examiner’s office. North Carolina’s last complete year of finalized overdose death data is 2022.

“We’re almost at the end of 2024. It’s not fast enough,” Mary Beth Cox, an epidemiologist who tracks substance use at the North Carolina Division of Public Health told a meeting in September.

Because there will always be some lag in the data, researchers like Cox look to some early indicators, such as emergency department visits, to track the state’s progress in addressing the overdose crisis. Since 2018, her department has been putting out monthly reports on overdose trends seen in emergency departments across the state. The latest report shows emergency department visits are down consistently in 2024 over the same period of time last year. For example, 1,055 overdose visits were while 1,518 were reported in August 2023.

Another early indicator researchers look at is 911 calls seeking help for an overdose. Nationally, that those calls are down 16 percent in October 2024 from October 2023.

But these systems don’t paint a clear enough picture, Cox said.

“If we're seeing a decrease in [emergency department] data, does that actually mean a decrease in overdoses? We don't know. It just means people aren’t going to the [emergency department],” she explained. “If we see an increase in [emergency department] visits, you might say, at face value, that's a bad thing. But it could mean more people are getting connected to care.”

“Without the death data to supplement, it's really hard to know what's going on,” Cox said.

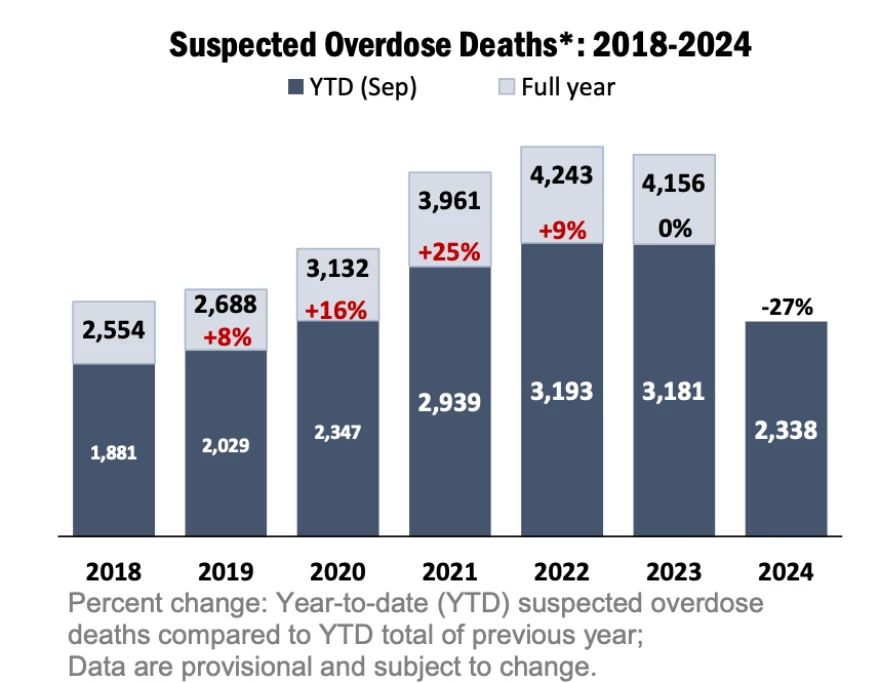

Her team has worked with the chief medical examiner’s office to put out an additional report every month on . Their most recent report shows a in suspected overdose deaths in September 2024 from September 2023.

North Carolina Attorney General (now governor-elect) Josh Stein attended the meeting and applauded the group for their tireless work to address the opioid crisis. His office played a key role leading the multi-state legal challenges that resulted in $1.5 billion in opioid settlement money for North Carolina.

“We are starting to see some hopeful developments on the horizon,” Stein said in September. “Obviously, we are not naive. We know the work is not done. There is so much more to do. But it’s appropriate to see and appreciate that something is better today than it was yesterday because folks have been working really hard for that to happen.”

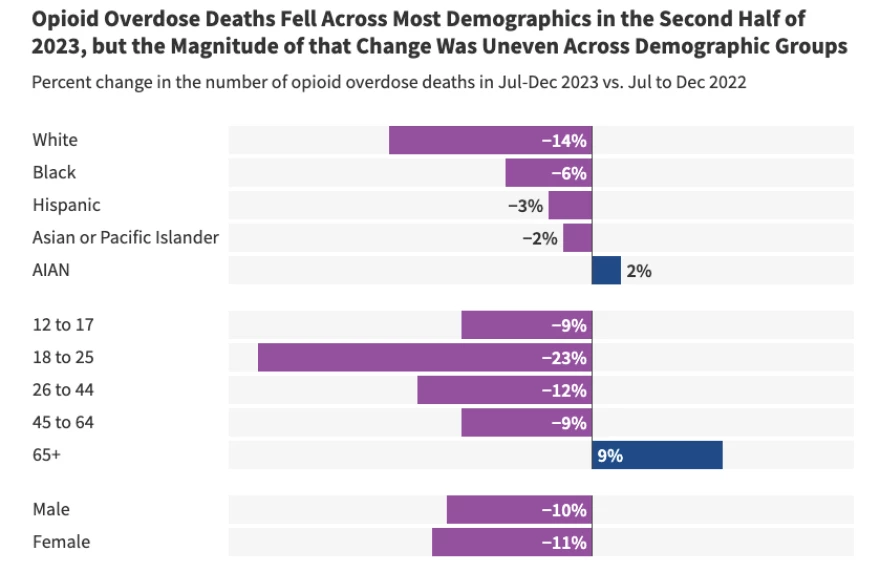

Cox cautioned that these decreases don't appear to be uniform across all demographics. “This is still very provisional data, very subject to change. But we're seeing it across multiple indicators that historically marginalized populations, particularly our Black communities, are still experiencing a slight increase.”

A recent ) found that white people have experienced the greatest drop in rate of overdose deaths, and Black and Indigenous communities are still battling disproportionately higher rates of overdose deaths.

While the overall trend offers glimmers of hope, Cox acknowledged the sobering reality behind the numbers — nine people are dying by overdose every day in North Carolina.

“That's a lot of people still,” Cox said. “Certainly we're headed in the right direction, but it's a whole lot of death.

“Every one of those deaths is preventable.”

Not the full picture

Those who work in harm reduction, like Michelle Mathis, executive director of , say the state's surveillance data fails to capture the reality they see on the ground. Mathis’ ministry serves people who use drugs in the foothills/Western Piedmont area of North Carolina. Olive Branch offers multiple fixed syringe exchange sites and mobile programs.

“The trends that we see — and when I talk to other agencies as well — they're not seeing this big downward reporting in overdoses,” she said.

She said that harm reduction workers always ask participants: Are you aware of any overdoses or have you personally experienced an overdose since the last time we saw you? Their answers are consistently recorded, but Mathis said the state health department only takes up that data once a year to include in an annual report.

“I have argued for this for as long as syringe services have been legal in the state. … We have to have some kind of monthly reporting mechanism,” she said.

Mathis said the majority of people that participate in Olive Branch’s exchange do not call 911 or go to the hospital when someone overdoses.

“Perhaps overdoses are not necessarily down, but people have access to more Narcan — because of harm reduction agencies — and so they are not as prone to being involved with EMS and the hospitals,” she said.

She added that a big reason her participants say they hesitate to call 911 during an overdose is fear of the state’s “, which has been strengthened by the state legislature since it was . The law allows prosecutors to charge someone with second degree murder if they sell drugs to someone who then dies of an overdose. Advocates say that the line between drug dealer and drug user is blurry, as people often buy and sell drugs from their friends and people they use with, who might not be what most would consider a “dealer,” per se.

Advocates say this law deters people from seeking help.

Brown, who has worked on advancing harm reduction efforts in Mitchell, Yancey and Buncombe counties, also said it’s hard to make sense of a reported drop in overdoses after witnessing the ever-changing illegal drug supply and people’s fear of potential death by distribution charges.

Why are overdose deaths declining?

These huge drops in overdose deaths being reported in North Carolina and around the country are puzzling to many. Substance use experts at the say that a 15 percent to 20 percent decrease in drug overdoses would be “unprecedented.”

“To our knowledge, no public health intervention in the United States has ever achieved this benchmark,” members of the lab . “Something has changed. And that this is happening without central coordination is a big deal. It has major implications for the way we think about overdose prevention interventions.”

Adams Sibley, social behavioral scientist with UNC lab, co-authored the lengthy blog post, which digs into the many leading hypotheses for the mysterious drop — from increased naloxone distribution to law enforcement operations at the border to removal of barriers to addiction treatment.

Sibley also presented to the NC Opioid and Prescription Drug Abuse Advisory Committee in September and said the decrease is likely a combination of many things, including the presence of xylazine in the street drug supply and a shift from injecting substances to snorting or smoking.

Xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer, is an additive that has been i added to fentanyl or heroin. It can cause nasty wounds and potentially deadly skin infections at the site of injection.

“There's a hypothesis that xylazine is one contributor to the drop in overdose deaths in a positive way,” Sibley explained. “Xylazine gives fentanyl legs, which means people may be using fentanyl less throughout the day because it's prolonging the perceived effect of fentanyl. Xylazine also causes these skin injuries, and so it might be encouraging people to switch to smoking.”

Switching mode of drug consumption from injecting to smoking or snorting is a harm reduction measure because people use smaller amounts of drugs at a time. And as the most common way people use drugs, according to the CDC. There are several reasons someone might switch to smoking, Sibley said.

“One is that if you've been injecting for a long time, you may not have a lot of places left to inject,” he said. “You might have scarred tissue, collapsed veins, abscesses, etc., and so smoking is a feasible option. The second reason is dose titration. It's easier to pace yourself when you're smoking as compared to when you're injecting. So this is a rational choice.”

Mathis said she has witnessed a shift toward smoking in participants of Olive Branch Ministry’s syringe exchange programs. She noted that the law that legalized syringe services programs does not allow for the distribution of smoking and snorting supplies.

“So we see — and we want to acknowledge — that change in mode of consumption is contributing greatly to this massive positive trend,” she said. “Yet state statute does not allow us to distribute the supplies which could really help boost this trend if we could legally do it.”

Sibley reminded the audience gathered in September that it’s important to stay humble, examine the data closely and listen to people who use drugs.

“We are not always in control of the numbers and the trends,” he said. “We know treatments are working. We know naloxone is working. But there may be reasons that overdose deaths are dropping that are out of our control.”

This first appeared on and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

North Carolina Health ����app is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at .