Annie Risku thought she had a lot to celebrate on election night, back in 2020.

She had just taken over as Wayne County's director of elections that July. And despite a pandemic, the state experienced historic voter turnout. In Wayne County, Risku's office successfully processed more than 10 times the typical number of absentee-by-mail ballots.

"We were so focused on COVID, preparing for the pandemic, keeping the voters safe, keeping their hands clean, keeping them from breathing on one another," Risku said with a wry laugh during a recent interview in her downtown Goldsboro office.

Then came the wave of intense skepticism about the elections process, including from voters in this county that Donald Trump carried. She says it caught her a little off-guard.

"We had, after 2020, a lot of individuals who didn't trust that we had actually counted all the votes," Risku explained.

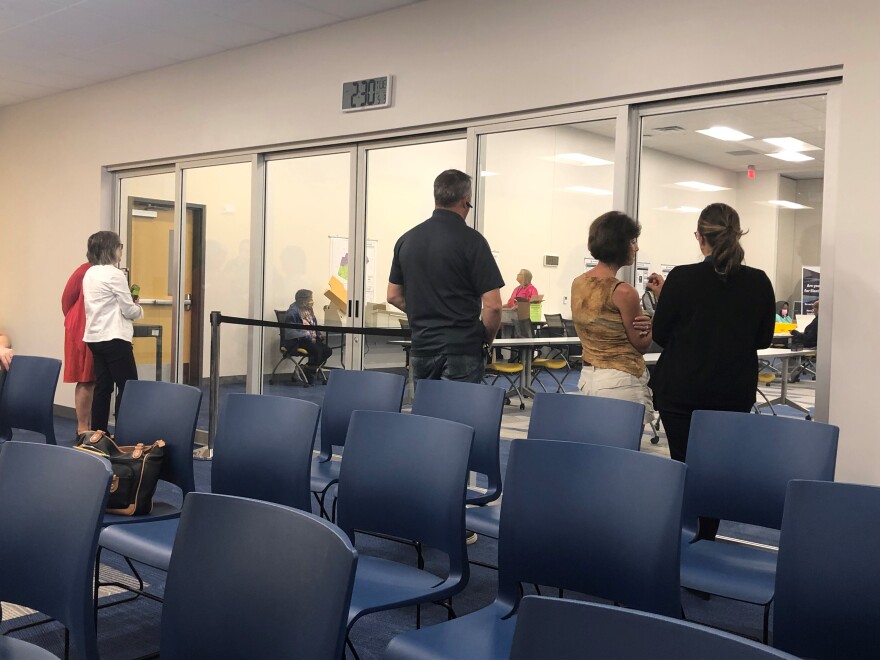

One woman demanded to enter her office to watch Risku count ballots, even though no such thing was happening or ever happens. Ballot counting is conducted according to state law in a prescribed manner and in public view. For example, county boards begin processing mail-in ballots at weekly meetings starting five weeks before Primary and General Election Day. And county boards hold public meetings to process ballots during the 10-day canvas period after Election Day, which culminates in the certification of official results.

"She refused to leave the building after extensive explanation that nobody's counting ballots, there's no ballot counting going on," Risku said, adding that she informed the woman that she could come to the public meeting that is held prior to canvas, the 10-day period after an election during which counties certify results.

Risku was forced to call the police to escort the woman from the premises. Since then, she has had more security cameras installed in the Wayne County elections building and an auto-lock function put on the front door.Personal attacks are taking a toll on elections administrators, survey shows

In Wake County, Deputy Elections Director Olivia McCall said her office also beefed up security in response to growing threats from the public in 2020, including posting an armed guard in the office's lobby.

"We had issues with stalking," McCall said. "There were cars parked adjacent to our facility with their lights off just watching."

Other incidents in Wake, according to McCall, include elections board members getting harassed on their way to their cars after meetings, and on election night in 2020, two individuals attempting to enter a restricted area where precinct officials were returning results to the county office.

"We are still addressing concerns that really amount to people just not understanding the elections process," said State Board of Elections Executive Director Karen Brinson Bell, who said a continuing flood of records and data requests to her office seem to point back to the certified 2020 election.

The state elections board had 229 public records requests total last year, according to NCSBE spokesman Pat Gannon, and there have been 125 so far this year. On top of that, the state board processed 382 data requests last year and already have received around 225 so far this year. Gannon said those all are historically high numbers.

Bell said many or most of those requests have a lot to do with questions about election results, voter data and demographics, and indicate a lot of misunderstandings about the way voter rolls are maintained.

"That we don't just open up the newspaper and rely on an obituary, that we work with the state vital records and our register of deeds and so forth to be official before we would remove a deceased person from the rolls," she explained.

But talking to Bell and other elections officials, it is clear that the most troubling thing about the brand of public mistrust to come out of 2020 is the ugly, personal nature of it. Bell described herself as a native North Carolinian from Duplin County and said people should remember that election directors and precinct workers are people you go to church with and pass in the grocery store.

"To receive emails from people who don't know me, and some of them have been just downright disgusting, making reference to my father's anatomy and how my parents came to produce me," Bell said. "What does that have to do with the job that I do?"

Attacks on their integrity are taking a toll on elections administrators nationwide, according to Liz Howard, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice, which recently .

"Election officials from across the country identified as one of the top two reasons for the likelihood that they're going to leave the profession prior to the next presidential election as the lies that are being spread by the elected officials about the elections process," Howard said.Much of the public mistrust is rooted in 2020 election lies

Even before the 2020 election, ex-President Donald Trump started sowing seeds of distrust in the process, baselessly claiming in stump speeches that the absentee ballot system was rife with fraud and that anything but a victory for him would be suspect.

Since then, partisan actors on the right have pushed for so-called forensic audits of results in places like Arizona and Wisconsin, swing states that went for President Joe Biden. In North Carolina, which went for Trump but also sent Democrat Roy Cooper back to the governor's mansion, hard-right lawmakers in the General Assembly threatened to bring armed law enforcement to left-leaning Durham County to seize and examine voting machines.

It was an empty threat that Durham Elections Director Derek Bowens took in stride.

"We came to the conclusion that the statute didn't permit that action and therefore we didn't allow it," Bowens said, referring to the GOP lawmakers' demand for access to the voting machines.

In light of such attacks on the integrity of North Carolina's elections system, Bowens said he takes comfort in knowing the state's elections administration is an open-book process.

"The question is," he added, "are you in a space where you actually want to receive what is true, or not?"Public interest in the elections process is a 'silver lining,' local official says

Voters who are curious or skeptical have ample opportunities to see the elections process for themselves. During the 10-day, post-election canvas period, voters can watch bi-partisan teams conduct hand-counts of ballots from randomly selected precincts. They also can watch absentee-by-mail ballots processed at county board meetings that start five weeks before election day. And before every primary and general election, the public may observe county elections boards put their voting machines and ballot tabulators through logic and accuracy testing.

As elections director for Buncombe County, Corinne Duncan said she sees increased public interest in elections as one of 2020's silver linings. The Buncombe County Republican Women's Club recently invited Duncan and her staff to talk about election integrity.

Duncan said she was confronted with strongly worded questions from the group, plus accusations and discontent over the fact that a photo-ID requirement for in-person voting had not been implemented yet in North Carolina. A mostly GOP-backed photo ID law for North Carolina has been held up by litigation. What is more, elections administrators in North Carolina enforce and apply laws but do not write them.

Duncan said the meeting with the GOP women's group had been scheduled for one hour but lasted two.

"And after that," Duncan said, "I had several people come up and say things like 'You changed my opinion about this.'"

The organizer for the Republican group declined an interview request but did write in her email that she was very impressed with Duncan and her team.

Peggy Defenderfer, a former schoolteacher, has volunteered to work polls in Wake County for almost 20 years. Now a chief precinct judge, she said she takes pride in helping voters fulfill their civic duty.

In an interview on her screened-in back porch the day before early, one-stop voting in this year's mid-term primaries was to start, Defenderfer said she noticed a heightened tension on voter lines in 2020 and that campaigners and electioneers handing out pamphlets seemed more pushy than usual.

But she came up with a method for dealing with that, a ritual she said she performs every morning at her polling site as she addresses everyone gathered outside.

"I say, 'OK, today we are here to vote, we are not here to antagonize anybody," Defendefer described. "'First of all we're humans, secondly, we're Americans and thirdly we are ensuring that our voters get to vote. So, if you're here causing trouble and irritating my voters, I'm going to come out here and I'm going to ask you to leave.' And I do have that power."

Defenderfer is registered as a Republican but said she doesn't identify herself with a partisan label. And she said she has had no trouble at her polling sites since she started giving her morning pep talks.

Risku, Wayne County's elections director, said she isn't ready to leave the profession, yet, but the attacks on her integrity are demoralizing.

"When you know that you're working weekends, when you know that you're working nights," Risku said, "You know, I'm salaried, so I don't get comp time, I don't get overtime pay. So when I'm here ‘til 11 o'clock at night that's because I want to make sure that the election is successful."

Risku added that if 2024 is a repeat of 2020 she might be looking at a career change. And the loss of experienced, dedicated public servants like Risku poses a greater risk to election security than phantom fraud conjured by partisan actors.