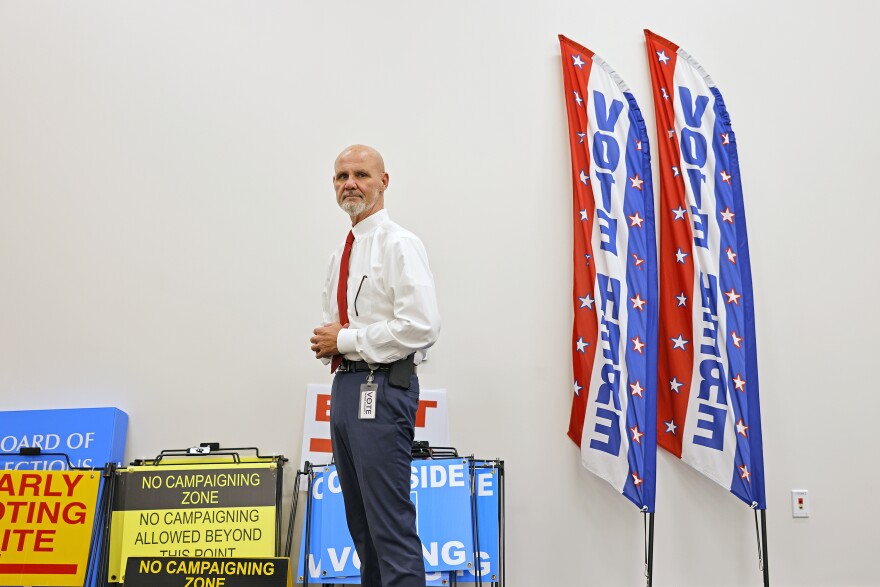

Gary Sims said he has never seen anything like the deluge of records requests inundating his and other elections offices across North Carolina and the country.

Sims is the director of elections for Wake County ÔÇö the state's largest in terms of registered voters ÔÇö and has been working in elections administration for more than two decades.

He called the steady stream of requests for records from the 2020 election, a surge that has increased since July, "organized and structured."

They come in the form of letters and emails with identical language, often seeking records that, in North Carolina at least, are deemed to be confidential ÔÇö like Cast Vote Records ÔÇö and therefore not open to the public. Those are documents that could be used to determine an individual voter's identity and how that person voted.

"I have a to protect that elections information," Sims, a U.S. Army veteran, said.

Elections official laments being seen as part of a 'rigged system'

Sims has been dealing with sweeping demands for a variety of paper and electronic records, including results tape ÔÇö long streams up to 30 feet long ÔÇö emitted from tabulators that show every vote cast on a certain day.

Just seven weeks away from the next election, when his staff is consumed with processing absentee ballots, registering voters, hiring and training precinct workers, Sims has had to make difficult choices about whether to divert resources to requests driven by a persistent but baseless skepticism about the 2020 results.

And Sims said that even when he tries to explain the elections process to a skeptic or why there might be a delay in fulfilling a records request for something that must be heavily redacted or may not be given out at all, he said the response can be disheartening.

"You know, 'I'm just part of this rigged system' or something like that," he says.

Timed as it is with the 2022 midterms, the records demands are placing a heavy strain on elections offices, especially in smaller counties in North Carolina with barebones operations of five or fewer full-time staff members.

"Any time you're distracting election officials from the critical business of administering elections you are increasing the likelihood of innocent but disruptive mistakes that could happen down the road," said Amy Cohen, executive director of the National Association of State Elections Directors.

Cohen said elections offices in jurisdictions across the country, whether they went for Joe Biden or Donald Trump in 2020, are seeing the waves of identical records requests.

'My Pillow Guy' issues a 'call to action'

Many of the records requests mirror put up by My Pillow CEO Mike Lindell ÔÇö a fervent Trump supporter and prominent 2020 election denier ÔÇö on his Frankspeech.com web site.

"We need all the requests for the Cast Vote Records in every single county across the United States," Lindell told his followers during his so-called "Moment of Truth Summit" last month. "That's your biggest call to action."

The event was caught on video that conveniently provided a promo code that could be used to buy Lindell's pillows and other products.

Another 2020 election denier and podcaster, Tore Maras, used her to provide a template for demanding elections records. Telegram is a social media platform described by the Southern Poverty Law Center as "a haven for neo-Nazis, white nationalists and antigovernment extremists" banished from more mainstream social networks.

An Ohio court recently kicked Maras off the ballot in the GOP primary for Secretary of State because of invalid signatures on her petition to run, in response to a challenge filed against her by an Ohio Republican Party official.

"I am an aggrieved citizen of the United States and of the State of North Carolina and I am contemplating filing a lawsuit against the relevant parties pertaining to the continuing concerns I have regarding the integrity of all elections that took place after December 31, 2019," the letter begins, using the same language in letters read to ╣¤╔˝app by the state's top elections official and two county directors and in hundreds of identical letters sent to elections offices at the state and county levels.

"Accordingly," the letter continues, "I hereby notify you and instruct you to retain any and all documents and other materials related to all post-2019 federal and state elections through the date of this letter and continuing thereafter."

"Well at this point it is very clear that it is a deliberate attempt to impede our work and probably to try to take our eye off the ball for the midterm election," said Karen Brinson Bell, executive director of the North Carolina State Board of Elections, referring to the scope and systematic nature of the many records requests.

... it is a deliberate attempt to impede our work and probably to try to take our eye off the ball for the midterm election.Karen Brinson Bell, executive director of the NC Board of Elections

Brinson Bell can be forgiven for sounding a bit exasperated when talking about the persistent skepticism surrounding the 2020 election, a race that was thoroughly audited and certified almost two years ago.

Not even a pandemic could suppress voter turnout in 2020. North Carolina saw a highwater mark of more than 75% turnout among registered voters. And then, as with every election, counties went through the painstaking canvas process to certify the results, including a hand-to-eye count of ballots from randomly selected precincts in each county and a reconciliation to ensure that the number of people who checked-in is equal to the number of ballots cast.

Under federal law, elections offices may soon shred 2020 elections records

In Wayne County, home to Goldsboro and Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, elections director Annie Risku recently walked into a smallish office that has been converted into a storage room.

The room was lined with metal shelving containing columns of rectangular cardboard boxes marked "ATVs" from 2020, referring to authorization to vote forms, attestations that every voter who casts a ballot must sign. On the floor were rows of larger banker's boxes filled with absentee ballot envelopes containing confidential voter information, also from 2020.

"This is supposed to be a workspace," Risku said of the converted office. "But we had to use it for storage because of the turnout from 2020, such high turnout we just didn't have room over in our warehouse for all the records."

As of Sept. 24, Risku and other elections officials will be able to free up critical storage space by shredding or otherwise disposing of records from 2020. Under ÔÇö absent court order ÔÇö federal elections records must be preserved for 22 months following certification.

Risku said she understands 2020 election deniers are liable to distort these otherwise routine administrative steps and take them as a sign of corruption. But she also said she finds such claims preposterous, noting that elections in North Carolina are overseen by administrators, bipartisan board members and precinct workers of all political stripes whose shared goal is preserving a fair and secure democratic process.

"In order for massive fraud to be committed, everybody in this would have to be complicit in it," she said.

A sign of what to expect for 2024?

Year to year, there are discrepancies in election results, random cases of double voting or even ineligible people casting votes due to a misunderstanding of the law. But these incidents occur at such a minute level that they have no effect on outcomes. And these miscast ballots and discrepancies get cleared up during the 10-day, post-election canvassing period.

In other words, Annie Risku pointed out, the system works.

"So we're continually auditing, we're continually doing research for provisional ballots, making sure that there's one vote cast for every voter," Risku said.

The only real example of widespread, systematic election fraud in North Carolina's recent history occurred in 2018. And that wasn't a case of voter fraud, per se. It was an absentee ballot collection and tampering scheme organized by Bladen County political operative McCrae Dowless, who died in April before his scheduled trial for obstruction of justice and illegally possessing ballots. Dowless was working for a Republican candidate in the 9th Congressional District.

It was a scheme that was successfully investigated and uncovered by the State Board of Elections. The 9th District scandal resulted in a redo and the successful election of Congressman Dan Bishop. Bishop is a Charlotte Republican who passionately supports Trump and voted against certifying Pres. Biden's 2020 election wins in Pennsylvania and Arizona.

What Wayne County Elections Director Annie Risku really fears is that the coordinated campaign of records demands inundating elections officials now is just a dry run for 2024, when Trump ÔÇö the election-denier-in-chief ÔÇö might seek the presidency again.